With the summer months upon us, many of us will spend more time outdoors and in the sun than we do at other times of the year. We have all heard the warnings about making sure to use sunscreen to reduce our cancer risk, but did you know that 1 out of 5 people will develop skin cancer by the time they reach the age of 70 years? There are two primary classifications of common skin cancers: melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Among the non-melanoma types, the most common are squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma and the deadliest is Merkel cell carcinoma. There are also more rare cutaneous adnexal carcinomas. Most people hear “skin cancer” and don’t realize there are so many types. What are the differences between them? To learn more about skin cancer, prevention, and research being undertaken by our own dermatopathology faculty at Michigan Medicine, we spoke with Dr. Rajiv Patel, the Director of Dermatopathology in the Department of Pathology.

The Dermatopathology Section in the Department of Pathology at Michigan Medicine is, according to Patel, “one of the best of its kind anywhere.” It is currently made up of nine clinicians, both dermatologists and pathologists who have received an additional year of subspecialty training in dermatopathology, working together to ensure patients receive the best possible care. Dermatologists are physicians whose focus is on the clinical presentation and treatment of cutaneous disease – what does it look like, feel like, what are the clinical presentation and test results (often including biopsy interpretation) telling me? The pathologist’s area of expertise is the laboratory-based perspective – what does the biopsy look like under the microscope, what are the right tests to run to make a definitive diagnosis? Both pathologists and dermatologists can specialize their training to become dermatopathologists focused on microscopic diagnosis of problems involving the body’s largest organ, the skin. By having both perspectives within the section, patients receive balanced and complete consideration with regard to the diagnoses made. “It is somewhat unique to our group that we have people from both backgrounds working together in the same section,” said Patel.

Among the four most common skin cancers, melanoma is the most lethal. Melanoma is a cancer that originates from the melanocytes. These are cells producing pigment in your skin. When you get a suntan, the melanocytes are reacting to the sun’s rays to produce more melanin and protect your skin from harmful UV light. Multiple factors, including over-exposure to UV light and genetic background can cause these melanocytes to undergo malignant changes and divide rapidly and uncontrollably, resulting in melanoma. People who carry certain genetic mutations may also be predisposed to melanoma. In addition to melanoma, there are also benign melanocytic tumors called nevi that behave in an indolent fashion and do not harm the patient.

Among the four most common skin cancers, melanoma is the most lethal. Melanoma is a cancer that originates from the melanocytes. These are cells producing pigment in your skin. When you get a suntan, the melanocytes are reacting to the sun’s rays to produce more melanin and protect your skin from harmful UV light. Multiple factors, including over-exposure to UV light and genetic background can cause these melanocytes to undergo malignant changes and divide rapidly and uncontrollably, resulting in melanoma. People who carry certain genetic mutations may also be predisposed to melanoma. In addition to melanoma, there are also benign melanocytic tumors called nevi that behave in an indolent fashion and do not harm the patient.

Due to its lethality, it is important that melanoma is diagnosed early and correctly separated from a benign nevus. In most cases, distinguishing between melanoma and nevi can be done reliably by a dermatopathologist using its microscope. Yet, as noted by Dr. Aleodor (Doru) Andea, director of the Dermatopathology Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory (DPML) at Michigan Medicine, some melanocytic growths are “ambiguous” – it isn’t clear by examining them under the microscope, or even looking at immunostained slides, whether or not they are cancerous.

The DPML is part of the Dermatopathology Section at Michigan Medicine. “The DPML focuses on pursuing new diagnostic and prognostic tools in melanocytic neoplasia and other non-melanocytic cutaneous malignancies [skin cancers] with a goal of developing and implementing innovative assays with demonstrated clinical value in the diagnosis of cutaneous malignancies,” explained Andea. The DPML offers state-of-the art molecular diagnostic testing for melanocytic tumors. The tests are intended to aid in the diagnosis of abnormal melanocytic growths that cannot be definitively classified as benign or malignant using visual microscopic criteria alone. Andea continued, “Such lesions are usually diagnosed using terms that imply various degrees of uncertainty in regard to their malignant potential and create the possibility for mismanagement including either over or under treatment.”

Members of the dermatopathology section at Michigan Medicine undertook a study to see if copy number variant (CNVs) found by Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) array testing might be correlated with melanoma as opposed to benign melanocytic cell changes. SNP array is a specialized molecular technique able to detect chromosomal copy number abnormalities across the entire genome and it is performed by DPML at Michigan Medicine. Their research, published in Modern Pathology journal discovered that melanocytic tumors with >3 CNVs were most likely to be cancerous as compared to those with ≤3 CNVs and established an algorithm for the diagnosis of histologically ambiguous melanocytic tumors. In a follow-up study, they compared the use of SNP array testing to the more conventional FISH testing and found that use of SNP testing with the >3 CNV cut-off, was significantly superior to FISH testing in terms of accuracy, sensitivity and specificity. These findings may aid dermatopathologists in making more accurate and complete diagnoses for patients.

Among the non-melanoma skin cancers, Merkel cell carcinomas (MCC) are the most lethal, but are relatively rare. Dr. Paul Harms, a member of the dermatopathology team, and colleagues have been studying this type of skin cancer and found that there are two different pathways that lead to MCC. The first, which was previously known, is driven by a virus called the Merkel cell polyomavirus. However, not all Merkel cell carcinomas were positive for this virus. Harms and colleagues found a secondary pathway where MCC formation is associated with UV damage in the absence of polyomavirus. Further research showed that in some cases squamous cell carcinoma in situ, also known as Bowen’s Disease, could, undergo a profound shift in cell morphology and epigenetic patterns, leading to MCC. His studies were published in Cancer Research and Modern Pathology.

Among the non-melanoma skin cancers, Merkel cell carcinomas (MCC) are the most lethal, but are relatively rare. Dr. Paul Harms, a member of the dermatopathology team, and colleagues have been studying this type of skin cancer and found that there are two different pathways that lead to MCC. The first, which was previously known, is driven by a virus called the Merkel cell polyomavirus. However, not all Merkel cell carcinomas were positive for this virus. Harms and colleagues found a secondary pathway where MCC formation is associated with UV damage in the absence of polyomavirus. Further research showed that in some cases squamous cell carcinoma in situ, also known as Bowen’s Disease, could, undergo a profound shift in cell morphology and epigenetic patterns, leading to MCC. His studies were published in Cancer Research and Modern Pathology.

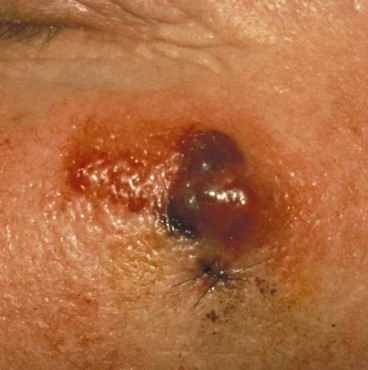

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common form of skin cancer and is usually found on sun-exposed skin on the face, neck, ears, scalp, hands, and arms. If not detected early, it can grow rapidly and metastasize (spread). Precursors to squamous cell carcinoma includes actinic keratosis, which presents as rough, scaly patches that develop as a result of years of sun exposure. Bowen’s disease is a very early form of skin cancer that is easily treatable. It resembles an actinic keratosis but is a type of early squamous cell carcinoma. It is sometimes referred to as squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Left untreated, however, it can become deadly. In a study published in Modern Pathology that included one of the first definitive molecular analyses of squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin, the dermatopathology team showed there is a surprising degree of genomic similarity between squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions; although UV damage is the first event in cancer formation, the trigger for progression to squamous cell carcinoma remains a mystery.

Basal cell carcinomas are the slowest growing and the most common skin cancers. Approximately 3.6 million people will be diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma each year. When caught early, almost all basal cell carcinomas can be successfully treated without complications. However, like other types of skin cancers, once the cancer has spread, it can be more difficult to cure. Treatment for skin cancers can include surgery plus or minus adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies such as radiation, immune system modulators like PD-1 inhibitors, or more targeted therapies such as BRAF inhibitors.

Basal cell carcinomas are the slowest growing and the most common skin cancers. Approximately 3.6 million people will be diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma each year. When caught early, almost all basal cell carcinomas can be successfully treated without complications. However, like other types of skin cancers, once the cancer has spread, it can be more difficult to cure. Treatment for skin cancers can include surgery plus or minus adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies such as radiation, immune system modulators like PD-1 inhibitors, or more targeted therapies such as BRAF inhibitors.

“Most skin cancer is caused by exposure to UV light, whether from the sun or from tanning beds,” said Dr. Patel. Patel, who attended medical school in Australia and then returned to Australia at the beginning of his career stated that tanning beds are “illegal in Australia due to the high incidence of skin cancer that they cause. Australia is the most UV-saturated place on earth due to a hole in the ozone layer. This, combined with colonization by largely fair-haired, fair-skinned people has resulted in very high levels of skin cancer within the population.” The government forbid tanning beds as these greatly increase the risk of developing skin cancer.

Since identifying melanoma early is key, Dr. Patel provided an easy-to-remember means of identifying them: ABCDE.

If you see such changes in a skin lesion, you need to consult with your physician, who may send you to a dermatologist for a skin examination. The dermatologist may then take skin samples or biopsies and send them to a dermatopathologist for review, and if you are lucky, that dermatopathologist will be located at Michigan Medicine!

As our interview was wrapping up, Patel was asked if he had a message he wanted to get out about skin cancer. He responded: