By Sara Talpos | Photography by Dustin Johnston | 19 June

Top Header: (Left to Right) Dr. Sriram Venneti, Abhijit Parolia, Adam Banda, Jill Bayliss, Pooja Panwalker, Chan Chung; Image Above: Research team with Tammi Carr at RunToughfor ChadTough.

Top Header: (Left to Right) Dr. Sriram Venneti, Abhijit Parolia, Adam Banda, Jill Bayliss, Pooja Panwalker, Chan Chung; Image Above: Research team with Tammi Carr at RunToughfor ChadTough.

Sriram Venneti’s lab explores the interface of metabolism, epigenetics, and brain development in order to better understand—and eventually treat—childhood cancer.

On a sunny afternoon in September, Tammi Carr stepped to the microphone to thank participants and sponsors of the 3rd annual RunTough for ChadTough race. The 5k and 1-mile fun runs received more than $80,000 in donations to help support pediatric brain cancer, a condition that has deeply affected the Carr family, which includes former U-M head football coach Lloyd Carr. The family has sought to draw attention to the experience of Chad Carr, Tammi’s son and Lloyd’s grandson. Chad died this past year of brain cancer. He would have turned 6 on the day of the race.

“We’re going to be releasing balloons before we start,” said Tammi. “It’s important to us to do that this year, to celebrate Chad’s birthday.” She paused, holding back tears, before adding, “He loved balloons.”

More than one thousand people were onsite for the run, including Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and neuropathology, and members of his lab. “It was so important for my lab to see this,” Venneti says, referring to Tammi’s introduction and follow-up comments from Carr family members. “Because you can play with these cells and create these mouse models, but what impact does your work have? Why is it important to do this?”

In the United States in 2016, an estimated 4,630 kids, ages 0-14, were diagnosed with some type of pediatric brain cancer. Venneti’s lab focuses on cancers that originate not in the brain’s neurons, but in the gluey support cells surrounding the neurons. These cancers are called “gliomas,” and for many patients, the prognosis is grim. Chad Carr, for example, had something called a diffuse pontine glioma (DIPG) that bears mutations in proteins called histones. According to Venneti, 90% of children die within one year of this diagnosis.

Brain cancers for children and adults are notoriously difficult to study because so many occur in regions of the brain that aren’t easily accessible to biopsy. As a result, treatment lags behind those available for other childhood cancers, such as leukemia.

Before his death, Chad Carr underwent thirty rounds of radiation at U-M’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. Most children diagnosed with brain cancer receive chemotherapy or radiation. But these treatments were developed for adults, whose tumors behave differently. Although Chad initially showed improvement, ultimately the treatment wasn’t enough. Venneti’s goal is to elucidate the mechanisms of normal brain development in order to better understand why and how cancer occurs.

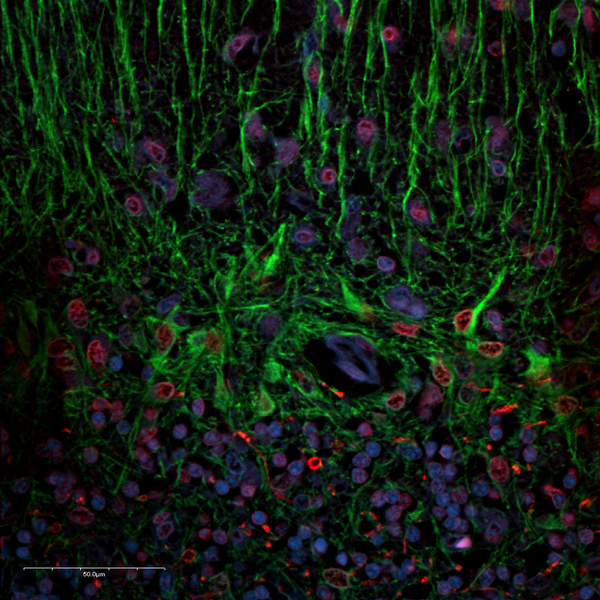

Neuronal stem cells termed radial glia in the developing cerebellum.Venneti has begun to make a name for himself by studying the interface of cancer metabolism, epigenetics, and brain development—an interface that ten years ago, scientists didn’t even know existed.

Neuronal stem cells termed radial glia in the developing cerebellum.Venneti has begun to make a name for himself by studying the interface of cancer metabolism, epigenetics, and brain development—an interface that ten years ago, scientists didn’t even know existed.

Seven years ago, when Venneti was a neuropathology fellow, researchers discovered a mutant enzyme present in the majority of adult gliomas. The enzyme was functioning within the Krebs cycle, a series of chemical reactions that transform nutrients into energy. The cycle is central to human metabolism. “That’s very surprising,” thought Venneti. “What is an enzyme mutation doing there?” Venneti was intrigued by this link between cancer and metabolism.

He decided to do his post-doc in New York City at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where he could pursue research to answer his question. “Life is full of serendipity,” says Venneti, describing his experience with science.

“You find this weird thing and then you follow it up.” While working in New York, Venneti discovered that childhood gliomas were quite different from adult gliomas. Specifically, childhood glial tumors exhibited different epigenetic markings.

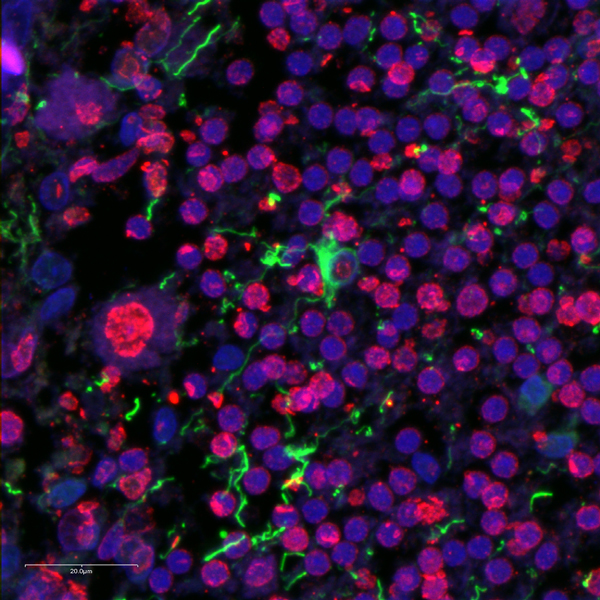

Neurons and supporting glial cells in the developed cerebellum.Epigenetics is a relatively new, exciting, and sometimes contentious field that seeks to discover how various biological mechanisms can switch genes on and off. “We think that epigenetics is really important for brain development,” says Venneti.

Neurons and supporting glial cells in the developed cerebellum.Epigenetics is a relatively new, exciting, and sometimes contentious field that seeks to discover how various biological mechanisms can switch genes on and off. “We think that epigenetics is really important for brain development,” says Venneti.

An emerging body of research suggests that many childhood brain cancers are related to epigenetics. For example, some pediatric brain tumors have mutations in the enzymes that modify histones, the proteins around which DNA is wound like a spool of thread. Other pediatric brain tumors have mutations in the histones themselves. And in other cases, the byproducts of cancer cell metabolism modify the tumor cell’s DNA and histones.

Venneti and his team are working to understand how epigenetics drives pediatric gliomas, how metabolic byproducts influence epigenetics in these tumors, and how this relates with normal brain development. For his efforts, he has already been awarded four prestigious grants: a K08 award from the National Cancer Institute, a Sidney Kimmel Scholar Award, a Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award, and a Matthew Larson Award.

Andrew Lieberman, MD, PhD, the Abrams Collegiate Professor of Pathology and Director of Neuropatholoy, describes Venneti’s work as “innovative,” and likely to yield information that will help define prognosis and guide therapies.

"We're trying to find patterns in the noise."

Stuffed dog that was given at ChadTough Run that the lab uses as their mascot.Venneti is excited about the possibilities for his research, but it’s the interactions with families like the Carrs that keep him motivated. “We’re only as good as our hypotheses and nature is always much smarter than us,” he says. “We’re trying to find patterns in the noise. Science can be very depressing, so it’s important to understand why we do it.”

Stuffed dog that was given at ChadTough Run that the lab uses as their mascot.Venneti is excited about the possibilities for his research, but it’s the interactions with families like the Carrs that keep him motivated. “We’re only as good as our hypotheses and nature is always much smarter than us,” he says. “We’re trying to find patterns in the noise. Science can be very depressing, so it’s important to understand why we do it.”

Most recently, Venneti was chatting with a couple, Lisa Carolin and Suzanne Murray, who were selling bread at the Ann Arbor Farmer’s Market. Venneti learned that in 2010, Lisa’s son had died of an aggressive glial brain tumor at the age of 15. The boy requested that his brain be donated for research. His guitar is now permanently installed in U-M’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital with a plaque dedicated to his memory.

“More than all the minutia of science,” says Venneti, it’s these human connections that matter to him: “That’s what gets me out of bed in the morning.”

▬

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Illustration representing the various machines and processing used within our labs. 2024Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Rendering of the D. Dan and Betty Khn Health Care Pavilion. Credit: HOK 2025Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.